Photo: Tacoma Preservation Society

The SBT industry is an Australian success story pioneered by the Port Lincoln fishing industry. From humble beginnings, to over-exploitation and accompanying species collapse, today the SBT industry is sustainable-certified and is the single most valuable sector of South Australia’s aquaculture industry (PIRSA, 2012).

THE BOOM

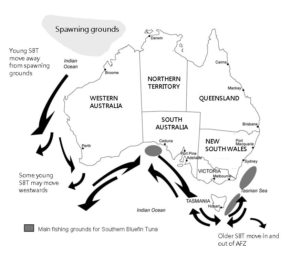

The SBT industry began towards the end of World War II, in 1936, when Stanley Fowler from the Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) “hitched a ride” with a Royal Australian Air Force flight over the Great Australian Bight. Stanley Fowler was conducting a survey of tuna in order to stimulate economic development. Before this time the fishery was largely unappreciated and unexploited (Serventy, 1956). It was during this flight that Stanley Fowler spotted abundant schools of SBT migrating off the coast of SA.

Unfortunately, the survey was put on hold when the survey vessel, F.R.V. Warreen was commissioned by the Royal Australian Navy for the World War. At the end of the war, the SBT fishery survey was continued using the F.R.V. Stanley Fowler. The first commercial SBT trolling fishery is believed to have started in 1949 (Serventy, 1956).

In the 1950s the South Australian government financially supported the building of the purse seine vessel the F.V. Tacoma, in Port Fairy, Victoria (Plevin, 2000), from where it made its way to Port Lincoln. After a series of start-up issues, the F.V. Tacoma successfully caught its first load: an astonishing 10 tonnes of SBT. This first catch was destined for the local cannery in Boston Bay near Port Lincoln.

The South Australian government foresaw the value in this industry and initiated a survey of tuna fish stocks using the F.V. Tacoma and fishing expertise from the United States of America. The survey revealed that masses of tuna schools passed through the Great Australian Bight; thus, highlighting a relatively unexploited, valuable industry.

In the years following there was an influx of European immigrants, particularly from Croatia. These immigrants led the expansion of the fishing industry in Port Lincoln. By the early 1960s Australia was catching 8000 tonnes of SBT using the line and pole method.

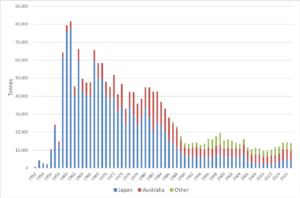

In the late 1970s, Australia reworked the industry to drastically improve fishing efficiency. Fishing method moved from poling to purse seine fishing (in short – surrounding the school of fish with a net). Boat design changed from US to Norwegian design, which was better suited to the rough waters of the Great Australian Bight. Chumming boats (release bait into the surrounding ocean) in combination with purse seine boats enabled greater catch of fish by pooling them together. Spotter planes were introduced to locate schools of SBT from the air and direct vessels to their location. The combination of all of these components increased the SBT catch to an unprecedented mass. In 1982 the Australian catch peaked with 21,000 tonnes. (See “From Ocean to Plate” for more information on fishing methods)

THE BUST

In 1979 fishery biologists warned that the fishery was fully exploited. The parental biomass was found to be reducing at an alarming rate (30% of its pre-exploitation size), which would ultimately result in poor recruitment of juvenile SBT to the fishery in subsequent years. Furthermore, there was evidence that the overall global SBT catch was beginning to decline. Australia SBT catch peaked in 1982; however, at the same time the Japanese catch of 40,000 tonnes was half that of its peak in 1962. This highlights how overall the SBT stock was decreasing.

Despite warnings, the fishing pressure/effort continued into the early 1980s as fishing vessels continued to search the ocean for ever scarcer schools of SBT. In 1983 an Australian Government inquiry found that the fishery was biologically over-exploited and heavily over-capitalised (Geen and Nayer, 1989).

INTRODUCTION OF QUOTAS

Upon realisation of the drastic effect that the tuna industry had on the species biomass, the industry as a whole changed its practices to support fishing of tomorrow, not just today.

In 1984, Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs) were allocated by the Australian Government to fishermen. ITQs were introduced to prevent further exploitation in the industry, allowing time for the species to recover. Japanese and New Zealand governments also agreed to limit catches.

After introduction of the initial ITQs, they were further reduced. Between 1983 and 1988 fishermen were unable to catch even the lower quotas, demonstrating how much the fishery had been over-exploited. In 1989 a trilateral conference was held between the three main nations fishing for SBT: Japan, Australia and New Zealand. At this conference it was agreed that the total combined yearly quota for all three countries would be limited to 11,750 tonnes. This was 8,000 tonnes below the peak of Australia’s SBT catch and 30,000 tonnes less than Japan’s peak catch.

In 1994 the informal management of the SBT fishery between the three countries was formalised with the signing of the Convention for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT). Since then CCSBT has managed the fish stock internationally. Today there are eight member countries of the CCSBT: Australia, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, the European Union and South Africa (CCSBT, 2013).

In 2011, a harvest strategy was put in place by the Australian Government. The harvest strategy involved the collection of data to contribute towards stock assessments conducted by an international scientific committee. From these stock assessments, CCSBT could make informed adjustments on quota.

The introduction of ITQs proved to be very effective in recovering the species biomass. In early September 2014, the CCSBT Scientific Committee confirmed that the latest data indicated a strong recovery of SBT. Today the spawning biomass has been confirmed to be at a sustainable level, enabling quotas to be increased.

FROM CANS TO SASHIMI

Increasing development in technology allowed SBT to be frozen at minus 60C. At this temperature SBT can be frozen in prime condition since super-cooled freezing stabilises fats in flesh thus preventing degradation. As a result, the SBT could be transported to Japan in prime condition, marking the birth of the sashimi market. SBT went from being worth $2 per kilogram in cans to greater than $45 per kilogram as a premium culinary product.

TUNA RANCHING

It was originally the Japanese interest that proposed ranching of SBT. In order to assess the potential of growing out SBT in ranches, a study was initiated by the Tuna Boat Owners Association of Australia (now called ASBTIA) and the Federation of Japan Tuna Fisheries Co-operative Associations in conjunction with the Overseas Fishery Cooperation Foundation (OFCF). The project was supported by the South Australian Government and the Australian Government and undertaken by the SBT industry in partnership with the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC). Brian Jeffriess, now chief executive of the ASBTIA, was the lead investigator and it was also one of the first projects for Patrick Hone, now executive director of the FRDC.

On the basis of this study, the industry began ranching SBT. Tuna ranching enabled the industry to grow out the smaller-sized fish travelling past Port Lincoln to a marketable size. In addition, it enabled harvesting of fish when they were in their prime condition i.e. with lots of fatty reserves.

On the basis of this study, the industry began ranching SBT. Tuna ranching enabled the industry to grow out the smaller-sized fish travelling past Port Lincoln to a marketable size. In addition, it enabled harvesting of fish when they were in their prime condition i.e. with lots of fatty reserves.

Originally, individual SBT were caught by poling, kept in the wells of their vessels and transported to pontoons in Boston Bay, SA. Local fisher, Dinko Lukin introduced tow pontoons, allowing SBT to be purse seined in large numbers, then towed to ranching pens.

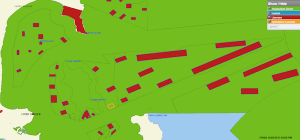

The pens were originally located in Boston Bay; however, a major storm in the Port Lincoln area in 1996 wiped out all the SBT stocks being ranched in the bay. The industry had to reallocate the ranches to deeper water in the lower part of the Spencer Gulf.

Today, 12 companies ranch Southern Bluefin Tuna in around 100 pontoons in the Lincoln Offshore Aquaculture Zone (inner and outer sectors). A public map is available to view lease site locations via the PIRSA website, visit – www.pir.sa.gov.au

Since ranching begun, the industry has steadily expanded to produce up to 9,000 tonnes of gilled and gutted SBT annually with an estimated annual value of between AUD$150 – AUD$300 million (PIRSA, 2012). Direct and indirect employment in Port Lincoln is over 1500 Full Time Equivalents (Econsearch, 2007).

Tuna ranching is a momentous success story for Port Lincoln. At the time it was first proposed many experts in the area said that ranching wild SBT would be impossible. However, against all odds and through years of trial and error Port Lincoln tuna ranching is one of the most successful aquaculture sectors.